What is MindLog™ for Educators?

MindLog is a sophisticated journal-like learning tool that supports students' mental development while creating a visual record of their development over time. It is the first tool of its kind, backed by more than 100 years of research. You can learn more about the thinking behind MindLog by reading MindLog for Educators‚ What's it all about?

Beyond educational testing

MindLog ushers in a test-free, domain-independent, student-centered, and growth-enhancing way of demonstrating learner development.

As a growth tracker, MindLog features an unprecedented level of utility, reliability, and predictive validity.

As a cheating detector, MindLog, when used as intended, both detects and discourages cheating. In fact, we suspect it's the best cheating detector in existence.

As a learning tool, MindLog:

- directly supports mental development while helping students build any kind of skill, including skills required for self-awareness, self-regulation, social interaction, learning, writing, reading, mathematics, reasoning, perspective seeking, collaboration, communication, argumentation, decision-making, research of all kinds, and more (depending on the prompts students are asked to respond to);

- allows educators to monitor the developmental impact of curricula by observing variations in students' growth trajectories;

- provides students with information about their own learning that will help them build skills for driving their own development;

- provides parents/guardians and educators with helpful insights into students' development; and

- incrementally enhances educators' maieutic skills. (See note below.)

Perhaps most importantly, MindLog produces most of these effects even in struggling schools or schools in which educators are minimally involved in its use, which means that there is no need for universal educator buy-in.

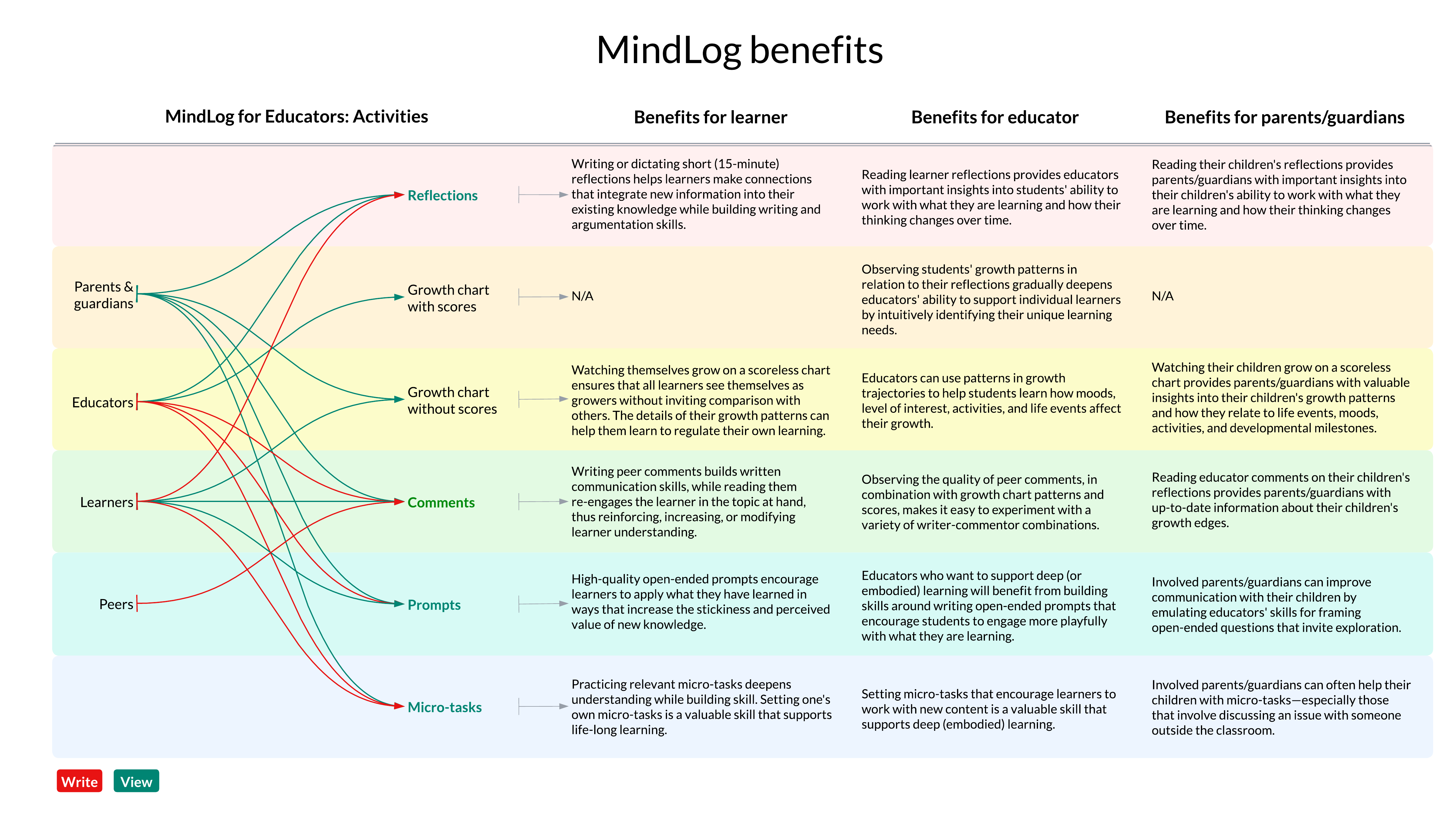

Lectica's post-Socratic version of the “maieutic” method differs from the Socratic form in one important way. Socrates used his version to lead students to predetermined “truths.” Lectica's version does not require a pre-determined truth. In fact, MindLog is designed to develop the mind through skill-building. This means that instead of asking, "What is the next fact this student needs to know?" educators using MindLog are more likely to ask, “What is an engaging practice that would help this student take the next step in developing per skills?” For example, in the educator's comment field of the example report shown below, the educator, based on the student's response, has targeted skills related to “perspective seeking” and possibly, “explaining findings.” Practicing these skills will not only develop skills for perspective seeking and explaining findings, it is also likely to enhance Francis's conception of a good education.

How learning really works

How does MindLog work?

MindLog records students' weekly reflections throughout the school year. Reflections typically relate to aspects of what students are learning at the time. Reflection prompts, which are written by educators or provided by Lectica, are designed to help students integrate new knowledge and skills into their current mental structures while providing Lectica with the kind of data required to determine students' current levels of understanding and skill.

MindLog provides developmental benefits from day 1. Benefits multiply as educators experiment with prompt writing and learn, through practice, how to use student reflections to provide optimal maieutic support, in the form of micro-suggestions, for each learner.

A micro-suggestion is a learning prompt that's designed to help a particular student enhance per understanding or build upon existing skills.

Making entries and viewing results

To make an entry in MindLog, all students need to do is sign in to Lectica, select an educator and class, then dictate or type a prompt name (optional) prompt, and reflections into an online form. If English is not their first language (and they speak a relatively common language), they are welcome to enter reflections in their first language.

After reflections have been submitted, educators can provide comments on individual student responses. Students are able to view these comments as soon as they have been released by the educator.

Note that we use the word “can” here. Although students will benefit more from using MindLog if their educators are able to make comments and/or suggestions, there are other ways to build on student learning. For example, students could be encouraged to comment on one another's reflections or discuss their responses with other students or a parent/guardian.

The peer commenting feature of MindLog enhances learning by allowing learners to collaborate in supporting one another's learning. Peer commenting is a valuable skill, and

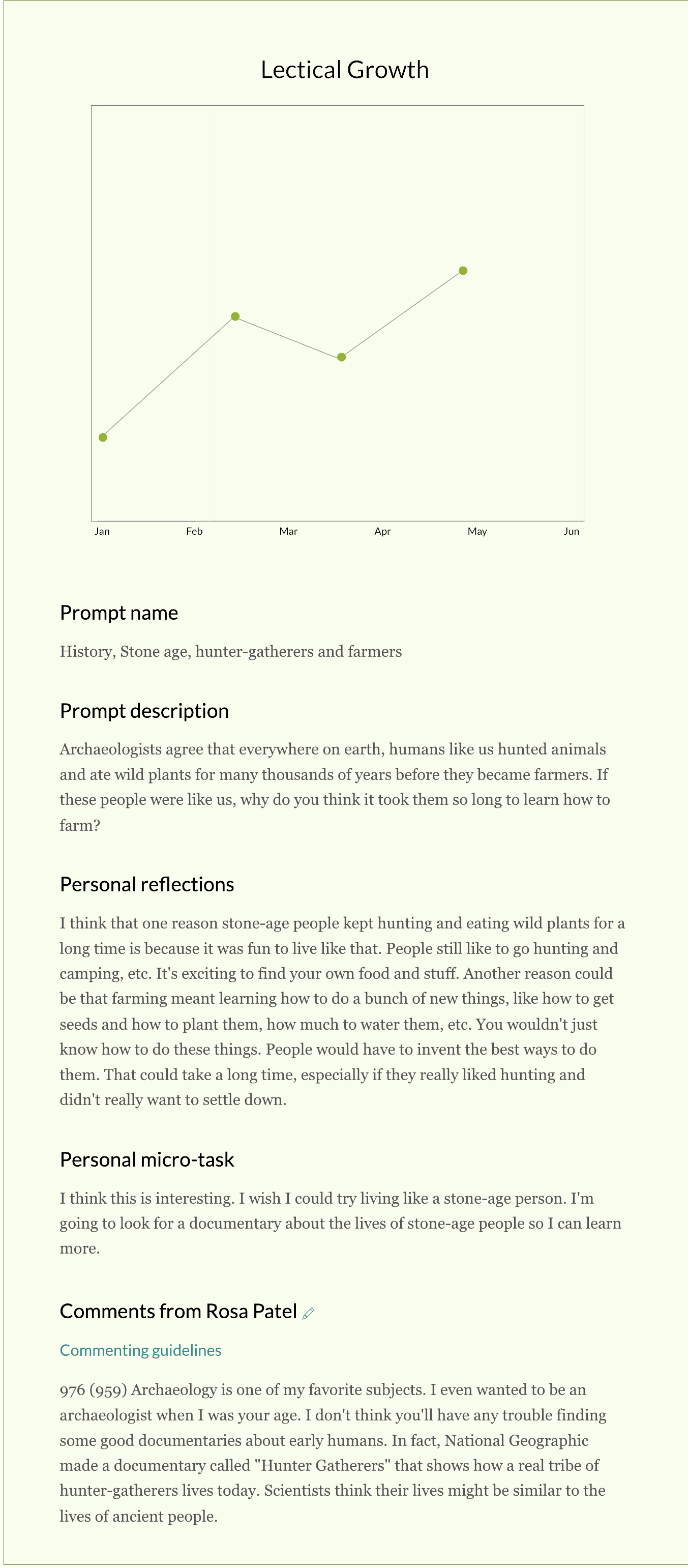

After about 6 months, students are shown their growth chart whenever they view the report for a particular entry. Below is an example report page showing a prompt, a response, educator comments, the students' chosen micro-task, and a growth chart. Note that there are no scores on the chart. This is intentional.

Observing and evaluating student growth

Educators working with MindLog are provided with a dashboard that displays their students' growth charts. They can view the chart of a single student, an entire class, or all of their classes. They can also filter results by school subject to compare growth in different knowledge areas, or group charts by dragging and dropping them into desired locations. For example, educators might create a group of students who appear to be struggling or multiple groups of students working on different projects.

The scores in MindLog growth charts are called Lectical™ Scores. The Lectical Scale is a refinement of Dr. Kurt Fischer's Skill Scale, a developmental scale that covers the human lifespan. Lectical Scores are provided by CLAS, Lectica's electronic scoring system. These scores tell us where a written text lands on the Lectical Scale. Educators do not need to understand the Lectical Scale in order to work effectively with MindLog. Simply working with MindLog will, over time, provide educators with an embodied understanding of development that is far more valuable than any academic understanding.

The growth charts for educators provide useful information about students' mental growth and wellbeing. In the figures above, we show growth charts for two students in the same school, both of whom are in grade 7. As you can see, Janet is quite a bit ahead of Chen, having performed at Chen's current level in grade 6. However, Chen's growth trajectory is a bit steeper. Moreover, while Chen is plugging along at a steady rate (with the exception of small disruptions in November and December each year) Janet's growth trajectory actually declined in late 2023. Declines like this can be early indicators of psychological distress or challenging life changes. MindLog's growth curves can provide evidence of emerging problems that students, educators, and parents/guardians can learn from.

Growth charts for students

MindLog is not designed to encourage students to compete with one another. Consequently, the growth charts presented to students show similar results—in the sense that all students who are growing see a chart that shows they are growing. In other words, they see evidence that that their learning efforts are having the desired effect.

Moreover, although Chen and Janet's growth trajectories are not actually the same, we show growth trajectories with a similar slope. Charts presented in this way are less likely to foster competition, and more likely to get students thinking about the details of their growth process—in other words, we want students to wonder why their scores go up and down so they can begin to connect these trends to their lives, feelings, behavior, and learning skills.

Low effort and “augmentation”

In the following modified version of Janet's growth chart, we illustrate two common anomalies—a sudden dip in scores and a sudden rise in scores. Sudden dips are generally caused by “blowing off” an assignment. Sudden rises generally result from some kind of external support—AI, grammar checkers, online searches, and help from friends or parents. Occasional blips of this kind can simply indicate that a student is feeling mischievous or having a bad day. Repeated instances of these patterns are more troubling. They may indicate that a student is struggling or feeling alienated.

Why focus on mental growth?

Conventional standardized educational assessments primarily measure correctness. Scores on these tests can go up or down and are readily compared to the scores of other students, but they don't tell us much about the quality of students' minds, such as how skillfully they can put their knowledge to work in messy real-world contexts. They also tend to narrow the way we think about learning—the things they measure become the important things to learn. Moreover, if we look closely at tests of correctness, we find that they are highly focused on one set of mental skills—skills for remembering. Unfortunately, a strong focus on skills for remembering leaves little educational time for working on many other skills required for optimal mental development.

In the mid 1990's Lectica's founder, Dr. Theo Dawson, decided that a high-quality and scalable measure of mental development would help educators strike a balance between skills for remembering and other critical life skills like those required for self-regulation, reflection, interpretation, deliberation, investigation, evaluation, social interaction, collaboration, perspective-taking, perspective-sharing, citizenship, and learning from everyday experience. She also decided that it was possible, given enough time and hard work, to develop such a measure. In the early 2000's Dawson demonstrated the feasibility of creating this measure, then immediately began designing the research required to go from feasible to real. CLAS—the accurate, reliable, fair, and scalable developmental scoring system that makes MindLog possible—is the outcome of that research.

At Lectica, when we use the term “mental development,” we're not just talking about thinking, knowing, and deciding. We think of mental development as the development of the mind as a whole, including its sensory, emotional, kinesthetic, and unconscious functions. We believe that learning always involves the whole person and works better when we actively invite the whole person to become involved.

Important MindLog requirements and conventions

- MindLog is designed exclusively to measure the mental development of humans. This means that it only works when students do their own work and make a reasonable effort to share what is on their mind. Doing their own work means no AI, no grammar checkers, no open-book entries, and no help from others.

- Users of MindLog for Educators are required to ensure that students do not use any outside sources or any form of AI when they enter their first few responses at the beginning of each year. This will make it obvious when students get outside help with future entries.

- There is one form of outside help that we permit. Students are encouraged to use a simple spell-checker. Misspelled words generally lead to lower scores.

- Students should write (or dictate) MindLog reflections about once each week. We place both upper and lower limitations on reflection frequency and word counts for practical purposes.

- Writing good MindLog prompts is a bit of an art. To help educators get started, Lectica provides a full year of standard prompts that cover math, the sciences, literacy, interpersonal skills, history & prehistory, the arts, and self-regulation. These standardized prompts also ensure that every mindlogging student has an equal opportunity to show off per learning during the first year. This provides a reliable baseline for every learner.

- Lectica also provides samples of prompts and several prompt templates for use following year one.

- Parents/guardians have access to student records through their children's accounts.

- Students are not able to view their scores directly. We strongly recommend that scores are not shown to students until they begin serious higher education and career planning in high school (ages 15-18).

- Schools must agree not to permit the use of growth charts or Lectical Scores in grading. However, the responses themselves can be graded in conventional ways. (Lectica plans to include rubrics for evaluating clarity and argumentation skills in a future version of MindLog.)

- When students come of age, they will become the sole owners of their own data. Prior to this, the parents/guardians have owner privileges. It is necessary for schools to establish their temporary custody of MindLog records with parents/guardians.

- Only four (sequential) student reports or responses can be viewed or downloaded at a time. This provision is required to protect Lectica's IP.

Within the first year of subscribing to MindLog, at least one educator in your school will be required to complete VIP (VCoL in Practice). This course not only introduces micro-VCoLing—the highly effective lifelong developmental practice MindLog is designed to support—but also helps educators build prompt-writing and commenting skills.

“Blow off” is an American colloquial term that doesn't seem to have a satisfying synonym in standard English. When we say that a student “blows off” an assessment, we mean “deliberately failed to make an effort” or “wrote something inappropriate.”

Prices & setup

Setting up MindLog can be relatively simple or quite complicated, depending on school and government policies, the size of a school, and how many educators choose to be involved. Pricing is less complicated. MindLog is a simple subscription service. Annual prices for MindLog itself are calculated per student, per entry. Additional administrative and consulting fees are billed on an hourly basis. We offer substantial educational and non-profit discounts for MindLog for Educators as well as most of our other products and services.

We are in the process of booking BETA engagements for the spring semester (in the northern hemisphere). Fifth and sixth grades only.

If you are interested in MindLog for Educators and would like to learn more, check out the links at the top of the page and/or fill in the MindLog for Educators interest form, below. (If you'd like a quick response, you can also contact us through our contact form.)